The late medieval western Mediterranean consisted of societies with slaves. Most of them were young women from the eastern Mediterranean for whom sexual exploitation was part of the daily experiences of slavery. Some male Italian slave owners tried to cover this up with a cloak of silence. Rare sources, such as an exchange of letters between slave owners, allow a limited view of sexual violence and the ensuing legal consequences.

The merchant Francesco di Marco Datini (1335–1410), founder of a complex “system of companies”[1] in the late Middle Ages, had one or two enslaved women in his household in Tuscany – as did many rich merchants of his time. Slaves were owned by persons, groups, and/or institutions. Datini’s companies on the shores of the western Mediterranean – namely in Pisa, Avignon, Barcelona, Valencia, and Palma de Mallorca – also owned and/or hired enslaved women on a temporary basis. Datini, his male employees, and other travelling merchants had sex with enslaved women, regardless of their marital status and whether the slave was their property or not.[2]

A Taboo Topic

In Catholic Christian societies of the 1400s, sex was supposed to serve a single purpose: procreation. Ideally, the next generation would be produced exclusively within the monogamous bonds of marriage. According to the authors of Christian moral literature (such as the penitentials), sex was a matter of timing. Husbands were advised to abstain from sexual relations with their wives on religious feasts, on weekdays reserved for penance and communal prayer, and when their wives were breastfeeding, menstruating or pregnant. Historian James A. Brundages’s “feeling randy?”-flowchart brilliantly visualises the regulation of sex in the Middle Ages. In fact, married couples who consciously observed the penitential rules “would rarely have been able to make love more than five times per month during their years of maximum sexual activity.”[3]

The married merchant Francesco Datini had sex with at least two women other than his wife Margherita: a servant and a slave. This was (and still is) considered adultery. For a bachelor like Manno degli Agli, manager of the branch in Pisa, to have premarital sex with (enslaved) women was seen as a lack of self-control in his role as ‘surrogate’ pater familias of the company household. Degli Agli had sex with at least two female slaves, one of whom was his own and the other belonged to the company.

In the merchant community, sex with slaves was not a ‘booster’ of masculinity, neither for Datini nor for degli Agli. It was “dishonest”[4], as degli Agli wrote to Datini, to communicate openly through correspondence about the expectations, lusts, and desires associated with sex with enslaved women. The topic of sex with female slaves was reserved for fleeting face-to-face interactions, not for lasting evidence in letters across time and space. At least in writing, the matter “had to be tacit.”[5] Men’s secrecy only worked until a slave’s sex work became noticeable in the form of a baby bump.

A slave’s pregnancy is not a reliable indicator of the frequency or nature of her sexual interactions, or of her level of participation and ‘consent’ under coercive circumstances. A slave’s pregnancy is only the visible tip of the iceberg of experiences of (violent) sexual (ab)use by male owners.[6] For the merchants, a slave’s pregnancy was always a question – of paternity, money, and power. For this reason, they could not avoid discussing sex with slaves in some of their commercial letters, today preserved in the Datini archive in Prato, Italy.

Lucia’s Sale Process

In the autumn of 1405, when the slave Lucia, sent from the branch in Valencia, was shown around in Palma de Mallorca by Datini’s employees, she had her tactics to sabotage the sale process by saying things that would put off potential buyers. First, she claimed to be Hungarian, a Christian by birth, and therefore off-limits to Catholic buyers. Second, she pretended to be mute or said she could not speak or understand the buyers’ language. Third, she claimed to be pregnant. In the end, Lucia’s self-fashioning as bad merchandise delayed the process for a few weeks, but did not prevent her from being sold to a certain Npingna from Menorca in December 1405.[7] About two months later it became clear that Lucia had not faked her pregnancy.

Rape in the Company Quarters

On 21 July 1406, Lucia gave birth to a son of whom Bartolino di Niccolò Bartolini, one of Datini’s employees, acknowledged paternity. The manager of the Mallorca branch, Niccolò Manzuoli, had doubts. According to him, in the week following Lucia’s arrival from Valencia, not only Bartolini but also Simone Bellandi, manager in Barcelona and on a short business visit in Palma, had “attacked her”[8] in the company quarters. Manzuoli’s choice of words suggests that Lucia was sexually assaulted twice within a few days by two merchants from the Datini community.

Why did two Italian merchants take the right to have sex with a slave they were supposed to sell on behalf of their colleagues in Valencia? Lucia was in a legal grey area, waiting to be transferred from the old, distant owner (the Valencia branch) to the new (yet to be found in Mallorca). During the transport and sale process, she passed through many male ‘hands’ – ship captains, merchants, notaries, to name but a few.[9] If a man did not want to take the blame for sexual violence, he could more easily hide behind other potential perpetrators (as Bellandi did). However, if a man wanted to acknowledge paternity in order to secure an heir, he could do so (as Bartolini did).

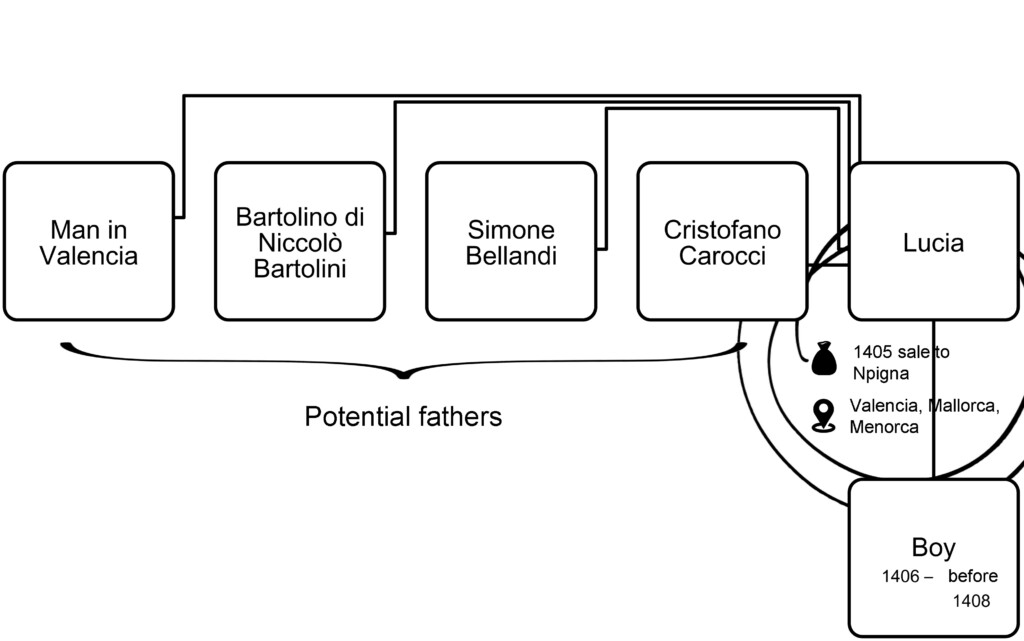

One Child and Four Potential Fathers

The question of paternity preoccupied the manager in Mallorca. In an age before DNA testing, Niccolò Manzuoli used the ‘mathematical method’ of calculating the period of conception based on the exact date of birth. His result: Lucia must have been impregnated by someone in Valencia before the rapes in Mallorca. Manzuoli thought of Cristofano Carocci, the manager of the branch there, who had sent Lucia to the Balearic Islands to be sold. Two years after the baby was born, another man of unknown identity arrived at Manzuoli’s door from Valencia, claiming to be the boy’s father, in competition with Bartolini.[10]

During and after her sale to Menorca, Lucia claimed to have had or rather to have been forced to have sex with three different merchants: Cristofano Carocci, Bartolino di Niccolò Bartolini, and Simone Bellandi.[11] The letters written by the merchants do not indicate how Lucia dealt with the emotional impact of repeated experiences of sexual violence (and/or instances of limited sexual agency). They only point out what the merchants were interested in: the fate of the boy born to the slave. Lucia gave (or was forced to give) her son to Bartolini.[12]

Denial of Motherhood

Although the details on this ‘handover’ remain elusive and it is not clear whether it actually took place, we can still wonder: Did Lucia suffer from being separated from her child, to whom she had formed an emotional tie? Was the deprivation of motherhood in a social sense another tragic blow in her life as a slave? Or is there a possibility that Lucia was relieved not to have to relive the (potential) trauma of sexual violence by raising the child she may not have wanted to conceive with a man she may not have wanted to have sex with in the first place?[13]

The situation had too many question marks, at least for the manager in Mallorca. Before the question of the paternity of Lucia’s child became a complicated legal affair between two men who desperately wanted the baby as a potential heir, Niccolò Manzuoli was relieved to announce that “the baby boy had died, so everyone [was] out of the matter”[14].

Conclusions

For the men of the Datini community, a slave’s pregnancy raised a number of questions – who was the biological father, who acknowledged paternity (which did not necessarily coincide), who took the child, and who covered it all up (if necessary). The answers to these questions were found in the peer group of merchants, sometimes in cooperation, sometimes in dispute – as in this case. It was only because the employee Bartolini, in competition with other potential fathers, staked an exclusive claim to the male baby of the slave Lucia that his colleagues made the sexual (ab)use of enslaved women in their warehouses a topic of their letter correspondence. According to the manager of the Mallorca branch, Manzuoli, Bartolini had “put his seal””[15] on Lucia. The manager’s wording equates sexual intercourse with a man’s ‘marking’ claim on a female slave’s body, whether she was his property or not. This claim could extend to the ‘products’ of the enslaved body, her children, whether or not biological paternity could be established. In the late Middle Ages, Italian slave owners became less interested in producing a new generation of slaves than in producing heirs – with enslaved women like Lucia contributing to the reproduction of the slave-owning class.

Lucia is one of many slaves sexually exploited by merchants from the Datini community. For the life stories of other enslaved women, see Corinna Peres’s dissertation “She wants to do it her own way.” Enslaved Women, Their Work, and Their Children in the Datini Merchant Community, 1380s–1410s (submitted at the University of Vienna), to be published soon.

Figures

Fig. 1: The graphic was inspired by the motifs of the sinopie painted on the façade of Palazzo Datini after the death of Francesco Datini and by a merchant letter from 1407 preserved in the Datini archive (code 314005).

Notes

[1] Federigo Melis, Aspetti della vita economica medievale (Siena: Monte dei Paschi, 1962), 108. “This system was a forerunner of the later holding company system and is considered Francesco’s most important contribution to business history,” cited from: Ann Crabb, The Merchant of Prato’s Wife: Margherita Datini and Her World, 1360–1423 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015), 34.

[2] For an introduction to the slave trade and slavery in the medieval Mediterranean, see Hannah Barker, That Most Precious Merchandise: The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260–1500 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019); Juliane Schiel and Stefan Hanß, eds., Mediterranean Slavery Revisited (500–1800) (Zürich: Chronos, 2014).

[3] James A. Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 160. See also ibid, 155–159, and Hans-Werner Goetz, Leben im Mittelalter: vom 7. bis zum 13. Jahrhundert (München: C.H. Beck, 1986), 60.

[4] Archivio di Stato di Prato (ASPo), Datini, Manno degli Agli to Francesco Datini, 28 October 1398, Pisa–Prato (code 1333). All translations are by the author.

[5] Sally McKee, “Slavery,” in The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe, ed. Judith Bennett and Ruth Mazo Karras (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 282. For different norms and practices in Spanish clerical and lay communities, see Michelle Armstrong-Partida, “Concubinage, Illegitimacy and Fatherhood: Urban Masculinity in Late-medieval Barcelona,” Gender & History 31, no. 1 (2019): 195–219.

[6] Emily A. Owens, Consent in the Presence of Force. Sexual Violence and Black Women’s Survival in Antebellum New Orleans (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2023), esp. 14, 17. Exploitation could also include non-reproductive sexual practices (‘sodomy’), such as “the coitus interruptus and non-vaginal penetration,” in Franz X. Eder, Eros, Wollust, Sünde: Sexualität in Europa von der Antike bis in die Frühe Neuzeit (Frankfurt a.M.: Campus Verlag, 2018), 259, translated by the author.

[7] ASPo, Datini, company in Mallorca to the company in Valencia, 4 November and 4 December 1405, Mallorca–Valencia (codes 125827, 125831).

[8] ASPo, Datini, Niccolò Manzuoli to Cristofano Carocci, 19 April 1407, Mallorca–Barcelona (code 314005). Niccolò Manzuoli’s letter of 1407, written in the mercantesca, a Gothic script, is accessible online: Fondo Datini Online.

[9] Christoph Cluse, “Genealogische Entfremdung: Zur Sklaverei in städtischen Gesellschaften Italiens (13.–15. Jh.),” in Unfreiheit und Sexualität von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Josef Fischer and Melanie Ulz (Hildesheim: Olms, 2010), 130.

[10] ASPo, Datini, company in Mallorca to the company in Barcelona, 26 October 1408, Mallorca–Barcelona (code 902529).

[11] ASPo, Datini, company in Mallorca to the company in Valencia, 19 November 1405, Mallorca–Valencia (code 125829); Niccolò Manzuoli to Cristofano Carocci, 25 February 1406, Mallorca–Valencia (code 519513).

[12] ASPo, Datini, Niccolò Manzuoli to Cristofano Carocci, 19 April 1407, Mallorca–Barcelona (code 314005).

[13] For a critical discussion of ‘motherhood’, see Chelsea Conaboy, “Maternal Instinct is a Myth That Men Created,” The New York Times, August 26, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/26/opinion/sunday/maternal-instinct-myth.html, accessed 10 April 2024. See further Élisabeth Badinter, L’amour en plus. Histoire de l’amour maternel XVIIe-XXe siècle (Paris: Flammarion, 1980).

[14] ASPo, Datini, company in Mallorca to the company in Barcelona, 26 October 1408, Mallorca–Barcelona (code 902529).For an emerging new research strand on female slavery and “constructions of maternity in the late medieval Mediterranean world,” see Debra Blumenthal’s current book project Comares. Mothering in Uncertain Times.

[15] ASPo, Datini, Niccolò Manzuoli to Cristofano Carocci, 25 February 1406, Mallorca–Valencia (code 519513).

Kommentar schreiben