Şalvar, Turkish baggy trousers, at first glance seem to be an apolitical fashion item. However, in 1980s Turkey, it became both an item of power dressing and part of a national self-orientalizing public image, reflecting women’s ambiguous position in Turkish society.

The şalvar, baggy trousers, played a contradictory role for women, especially considering international contexts. In the 19th century, it symbolized both a liberation of the female body and an orientalist vision of the harem. In 1980s fashion and style magazines for example the German-based Burda Moden, the depiction of şalvar highlights how this contradictory position re-emerged in perspective of local and global fashion trends in Turkey and Germany.

The politics of style magazines

The globally circulating Germany-based magazine Burda Moden was also published in Turkey. Until the 1990s, it was, however, not translated into Turkish. Instead, the original magazine was accompanied by a booklet in Turkish called Burda Kadın (Burda Woman), which did not contain translations of the German articles as one might expect, but original Turkish content on women, celebrities, or the family. It sought to present women as empowered through this content, while still being conservative in politics. Comparing the German magazine and the Turkish booklet, the imagery of şalvar in both editions reflects their similarity of aesthetics. At the same time, the lack of translation allowed for displaying the trousers in disparate ideological contexts, which are visible through the assemblage of design details, photographs, and texts.

Since the late 19th century, fashion and popular media coverages dealt with women’s changing status in society. This can be exemplified through the search for a genuine Turkish modernity in the Ottoman Empire and during the founding years of the Turkish Republic. Modernization was primarily understood as westernization, but a variety of Turkish actors sought to fuse it with invented or nationalized Turkish traditions.[1] While praising women’s visibility in the fashion industry, the media’s main goal was to transmit the image of a successful nation internally and externally, to the West. The şalvar shows the intricate symbolic and material relationships between clothing, gender and politics while recent research has focused mainly on the headscarf or veil.[2] Its depiction in magazines reflects how the (hierarchical) relationship between ‚the West‘ and Turkey was negotiated and performed through the representation of women’s bodies.

The şalvar – more than fashion

In the 1980s, the şalvar was reoccurring both in Burda Moden and Burda Kadın. This popularity is related to a certain fashion style: Power dressing was popular both in fashion shows and everyday attires. Garments like jackets with angular shoulder pads and matching trousers dominated the decade. The şalvar complemented this trend, even though it was flowy and not structured like the jackets. But the parallel occurrences of the trends do not simply demonstrate a transnational convergence in fashion style and taste. On the contrary, it reflects both a longer history of unequal exchanges between (Ottoman) Turkey and ‚the West‘, and the political project of 1980s Turkey as Burda Kadın’s focus was not only on fashion but also on society and women’s role in it.

Turquerie and emancipation

Women in Europe wore bloomers long before the 1980s in orientalised promenades and masquerades as an exotic item associated with the harem.[3] But the şalvar was also part of a more liberal fashion style for women’s bodies over the course of the 19th century and early 20th century: Corsets, encapsulating women’s bodies into one distinctive shape, were increasingly abandoned and pants (then also called divided skirts) offered more mobility for sports like cycling.[4] Şalvar’s name in English reflects this double identity, they are called harem pants and bloomers, named after the American women’s rights activist Amelia Bloomer (1818–1894), who has also fashioned these pants as a visual protest.

The history of the şalvar illustrates broader trends in how clothing styles from the Orient were appropriated in the Occident. They were never taken as a whole but as fragments, enabling their assimilation, and thus taming their foreignness.[5] These singularized items appropriated from the Orient were either matched with less ‚authentic‘ design elements or were exaggerated in their dimensions to be associated with being avant-garde in fashion. The former tendency reflects this need to tame by adding simplicity and structure, two characteristics historically associated with being western. This can be also linked to the century old tendency of objects from the Orient becoming luxury products, as for example the introduction of Kashmir shawls in the 18th century.[6]

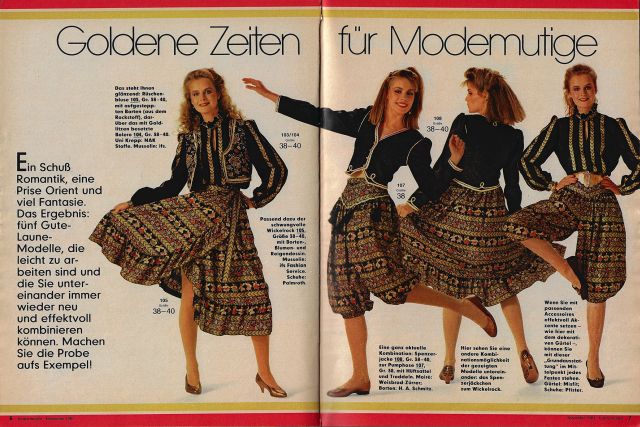

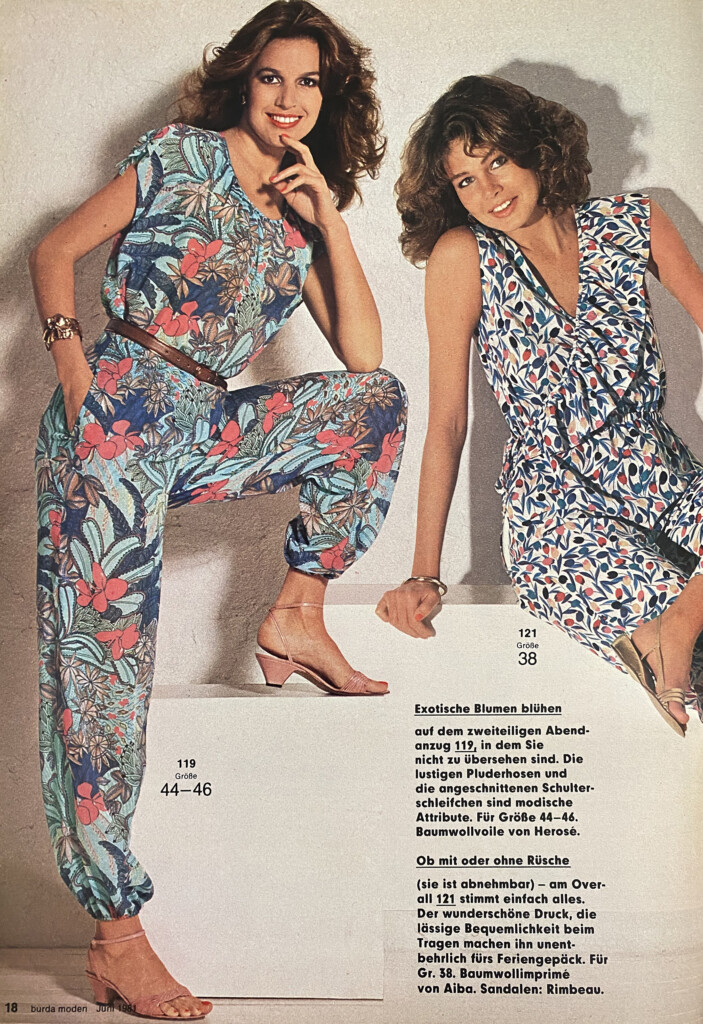

The issues of Burda Moden from the 1980s confirm this insight: the şalvar appears both as an everyday clothing item, and as part of an exotic costume. In some cases it is a mix of both achieved through an entertaining text combined with the way the depicted bodies perform. On the one hand, subduing their voluminousness and replacing the intricate embroidery with printed patterned textiles integrated them into everyday fashion (Fig. 2). On the other hand, adding gold and glitter accentuating shoulders and waist – as in global trends of the 1980s – associated them with either a costume or part of a lavish outfit, echoing the history of appropriation and transforming the trousers into objects of luxury from the Orient. The idea of luxury is commodified and attached to being feminine, mysterious, and exotic (Fig. 3).

Politics of representation

But the şalvar was not only featured in the German Burda Moden. It also appeared often in Burda Kadın, as for example in images from fashion shows in Turkey (fig. 3). These public events instrumentalized fashion and their designers to create a national image of Turkishness for the domestic market and for a western gaze alike. Historically, this can be linked to the „official nationalism“[7] projects since the nineteenth century. According to historian Şerif Mardin, the aims of these projects were „to free the Ottoman Empire of its inferior position in its relations with western powers“[8]. Following in these footsteps, Girl’s Maturation Institutes, since their foundation in 1945 as the first fashion schools, organized many diplomatic fashion shows. In 1981, for the centennial of Atatürk’s birthyear, the Ankara Girl’s Maturation Institute showed many şalvar designs which were described as modern versions of traditional clothes.[9] Since the Ottoman Empire’s modernization/westernization efforts (terms that were used interchangeably), women’s images became an instrument to demonstrate to ‚the West‘ that the Empire was part of the ‚developed‘ world.

This reoccurred in the 1980s, but in a different political context. The 1970s and 1980s were conflict-laden decades in Turkey. After years of economic decline and conflicts between nationalist and leftist groups, a military coup established a military junta in 1980, which controlled politics, restricted elections, and persecuted leftist and Kurdish political and civil society organizations. Despite this repressive context, feminists sought liberation beyond superficial emancipation during the 1980s. While women were given certain political rights, like equal rights to divorce and inherit, after the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, their private lives were still constructed to a great extent according to patriarchal relations until the civil code amendments in 2001. In the 1980s, women began to criticize the state and to demand civil and social rights. However, their role was ambivalent: Women and their protests were deemed unthreatening as a result of the ideological shelter provided by Republican state feminism. This meant that „women’s rights“ were decreed by the state in order to define the Turkish modernity and distinguish the newly founded Turkish Republic from the Ottoman Empire.[10]

Burda Kadın covered these fashion shows, which celebrated the mix of ‚the new‘ with ‚the old‘. (Fig. 4) Modernized traditional attires, as for instance the designs of Zuhal Yorgancıoğlu, became popular in the 1980s. This revival linked the post-junta Republic to the imperial Ottoman tradition, and – even more importantly – to Central Anatolia, the central reference point of Turkish nationalist ideologies since the foundation of the Republic. One can argue that Yorgancıoğlu’s designs reflect the attempts to modernize the şalvar by using plain white fabrics and by combining it with tailored jackets. Nonetheless, a closer reading of the attire reveals that the design references other historical models: The şalvar was indeed traditionally accompanied by the cepken, a short jacket worn by Ottoman women of different classes and ethnicities in the eighteenth century. These jackets were also worn in Anatolia before the Ottoman Empire. Fig. 3 also shows cepken, but designed with less embellishments. As can be seen from this only presumed modernization of the attires, the meanings attributed to modernization – and connected with it westernization – became blurry. The theorist and cultural critic Rey Chow tackles in her work the relationship between the ‚original‘ and the ‚translation‘ between cultures. She states that the assumed ‚original‘ is a construction based on the condition of „to-be-looked-at-ness“.[11] Yorgancıoğlu’s other collections reflect these ambivalent connotations while reproducing a harem phantasy as a commercial value, as her 2001 collection’s name suggests: The mystery of the east, the dream of the west.

Conclusion

Clothing is political, although it doesn’t manifest itself explicitly. The same clothing item can have various meanings through the context it is introduced in and through the design elements linking it to different historical and material contexts. While the şalvar became a clothing item representing female liberation for European women, it took on a different meaning for Turkish migrant women in countries such as Germany. As Monika Albrecht argues, the ‚female Anatolian village garb‘ distinguished women from Turkey from other migrants, when partners and families came to Germany in the 1970s.[12] When worn by women from the Turkish diaspora, the şalvar took on the meaning of ‚backwardness‘, helping to construct an exclusionary visual identity in urban life.

Meanwhile in Turkey, its reinterpretation offered a wishful space for women both as carriers and creators to play with the already ambiguous definitions of traditional and modern. In 1983, the Ministry of Culture prepared an illustrated album, which shows various costumes from every region and city of Turkey. Titled Local Turkish Costumes for Women and prepared in four languages, it was published to commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the foundation of the Republic and its aim was stated in the preface as: „Making known the local Turkish costumes, both within and outside the country.“ Moreover, it was added: „Turkish fashion designers, inspired by these local styles, have recently created a fresh current in fashion by modernizing these forms, colors, and designs.“ And the other aim was to leave this collection to future generations „who will reproduce them.“[13]

This album exemplifies how the mix of tradition and modernity became a celebrated formula in design practices in Turkey asserting the country’s and its designers‘ liminal position between the past and the present, between the Orient and the Occident. Through this position, women and their attire were instrumentalized to disseminate a public image that combined nationalism and tradition with modernity.

Anmerkungen

[1] Deringil, Selim. „The Invention of Tradition as Public Image in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1808 to 1908“, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 35 1 (1993), pp. 3–29; Hobsbawm, Eric. „Introduction: Inventing Traditions“, in: Eric Hobsbawm/Terence Ranger (eds.), The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1983, pp. 1-14.

[2] Lewis, Reina. Muslim Fashion: Contemporary Style Cultures. North Carolina: Duke University Press 2015; Vinken, Barbara. „Fashion and the Law: The Muslim Headscarf and the Modern Woman“, in: Djurdja Bartlett (ed.), Fashion Media: Past and Present. London: Bloomsbury Academic 2013, pp. 75-81; Cracuin, Magdalena. Islam, Faith, and Fashion: The Islamic Fashion Industry in Turkey. London: Bloomsbury Academic 2017; Gökarıksel, Banu/Secor, Anna. „Transnational Networks of Veiling-fashion between Turkey and Western Europe“, in: Emma Tarlo/Annelies Moors (eds.), Islamic Fashion and Anti-Fashion: New Perspectives from Europe and America. London: Bloomsbury Academic 2013, pp. 157-167.

[3] Inal, Onur. „Women’s Fashions in Transition: Ottoman Borderlands and the Anglo-Ottoman Exchange of Costumes“, in: Journal of World History 22 2 (2011), pp. 243-272, 251; Jirousek, Charlotte/Catterall, Sara. Ottoman Dress and Design in the West: A Visual History of Cultural Exchange. Bloomington. Indiana University Press 2019, 202.

[4] Jungnickel, Katrina. Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian women investors and their extraordinary cycle wear. Cambridge, MA: Goldsmiths Press 2018, pp. 55-76; Jirousek/Catterall 2019, pp. 202-206.

[5] Lehnert, Gertrud. „Zum Luxus fremder Dinge: Der Kaschmirschal“, in: Birgit Neumann (ed.), Präsenz und Evidenz fremder Dinge im Europa des 18. Jahrhunderts. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag 2015, pp. 302-322, 305.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Hobsbawm, Eric. Nations and Nationalism since 1780. Cambridge University Press 1992 [1990].

[8] Mardin, Şerif. Genesis of Young Ottoman Thought. Princeton University Press 1962, p. 60.

[9] Ankara Olgunlaşma Enstitüsü Dergisi. Atatürk’ün Doğumunun 100. Yılı Nedeniyle Özel Sayı. Istanbul: Tifdruk Matbaacılık Sanayii 1981.

[10] Abadan-Unat, Nermin: „Social Change and Turkish Women“, in: Nermin Abadan-Unat/Deniz Kandiyoti/Mübeccel Belik Kıray (eds.), Women in Turkish Society. Boston: BRILL 1981, pp. 5-31, 12; Arat, Yeşim/Pamuk, Şevket. Turkey Between Democracy and Authoritarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2019, 230-231.

[11] Chow, Rey. Primitive Passions. New York: Columbia University Press 1995, 180.

[12] Albrecht, Monika, „On the Invention of an ‚Essentialist View of Culture‘: Thinking outside the Prevalent Cultural Studies Discourse on Culturally and Ethnically Heterogeneous Germany“, in: The German Quarterly 89 4 (2016), pp. 395-410, 404.

[13] Local Turkish Costumes for Women. Ankara: Ajans-Türk1983.

Leave A Comment