This article explores how the concept of the New Ottoman Muslim Woman emerged through photography in early 20th century Istanbul. It examines how photography and print media offered Muslim women new agency to navigate modernization, and redefine their roles in the shifting socio-cultural landscape.

This post discusses the strategies and challenges involved in developing the concept of the New Ottoman Muslim Woman for my Ph.D. project. The New Woman has been conceptualized by several scholars as a global cultural phenomenon that emerged during the late 19th and early 20th century.[1] The New Woman transcends traditional roles, asserting her agency in public spaces through the use of photography, print media, and theater.

However, this concept has not been widely explored by Ottoman history scholars, partly due to the early monopoly of Western scholars over the concept and a lack of sufficient research on Muslim women’s visual practices.[2] In my dissertation, I aim to challenge the Eurocentric discourse on modernity with elements such as whiteness and Christianity at its core.

Instead, I shift my focus to technological innovations, such as photography and printing, as central drivers of social transformation. Consequently, I examine the role of photographic practices among Ottoman Muslim women in their processes of self-modernization, self-civilization, and self-representation.

Photography and the Ottoman Muslim Woman

After the introduction of photography in the 1840s, Ottoman Muslim women engaged with photographic practices in various roles: as objects of the gaze, subjects of the gaze, posers, observers, collectors, and photographers. Unlike non-Muslim women, who had greater access to public representation through theater, film, and print media, Muslim women had limited visibility. Photography offered a unique space for them to navigate these restrictions. Photo studios and personal photographic practices allowed Ottoman Muslim women to explore self-representation in both private and public spheres.

The Ottoman state, particularly under the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II (1876–1909), utilized photography systematically as a tool for knowledge production during the modernization process. The extensive photographic collection amassed at Yıldız Palace during this period serves as a rich visual record, reflecting the state’s role in shaping modernization efforts.[3]

However, the conspicuous absence of women in these albums complicates our understanding of their contributions to Ottoman modernization in the late 19th century. A fuller appreciation of Muslim women’s roles is possible only through engagement with photographic material from the early 20th century, when women gained the agency to publish their own images in women-led periodicals.

Conducting the Research

At the outset of my project, I searched for archives of Muslim women photographers in Istanbul from the early 20th century. However, the absence of such archives posed a significant challenge in uncovering how photography contributed to and shaped Ottoman Muslim women’s modernization experiences. Due to patriarchal norms, many women photographers were not recognized as professionals, and their works went often unregistered or lost.

This lack of archival material has necessitated creative, non-mainstream approaches to uncovering women’s agency. The concept of the New Ottoman Muslim Woman compensates for these archival gaps by analyzing other forms of evidence, such as women’s poses, postures, and participation in photographic practices, to reconstruct their active roles in creating and circulating visual narratives.

Staging the New Ottoman Muslim Woman

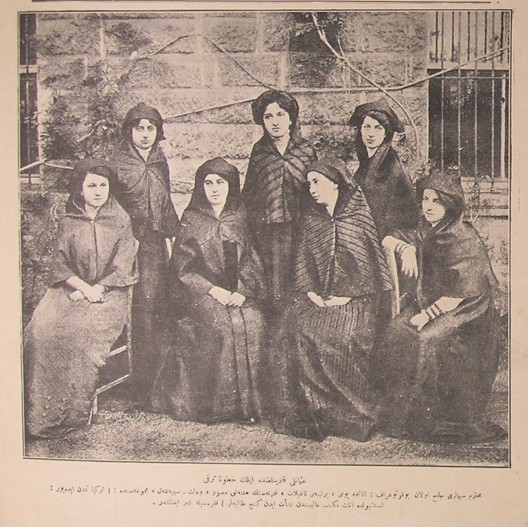

Women’s magazines played a crucial role in disseminating knowledge about Ottoman Muslim women’s photographic practices. In 1914, Kadınlar Dünyası (Women’s World) (1913–1921) broke taboos by publishing photographs of Muslim girls from Istanbul Girls’ High School (Dar’ül İnas) in its 117th issue (see Fig. 1), marking a milestone in Muslim women’s visual representation.[4] The magazine was published by the Ottoman Association of Defense of Women’s Rights (Osmanlı Müdafa-i Hukuk-u Nisvan Cemiyeti). The association was run by upper-middle class Ottoman Muslim women such as Ulviye Mevlan as the head of the association, Aziz Haydar (educator), and Mükerrem Belkıs (socialist and feminist).

The New Ottoman Muslim Woman appeared as an educated and working woman in the portraits of the magazine’s authors. After the publication of the photo of the Muslim girls in its 117th issue, Kadınlar Dünyası regularly published the portraits of its authors. They performed the New Ottoman Muslim Woman in these images. Her characteristics were defined by the three main goals of the Ottoman Association of Defense of Women’s Rights:

- Promoting women’s education,

- Advocating for women’s participation in working life, and

- Reforming Muslim women’s clothing.[5]

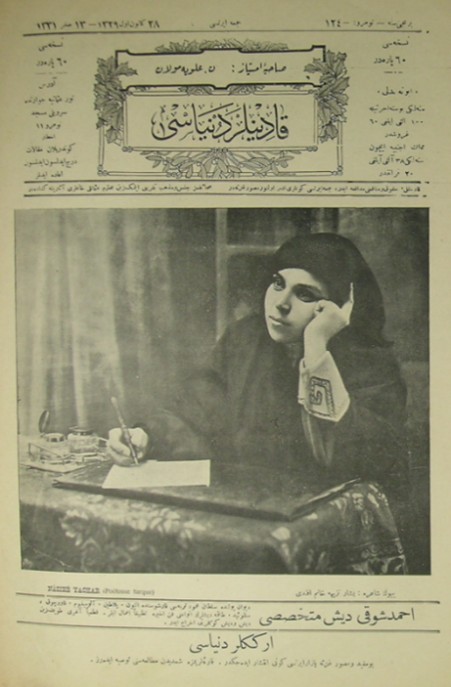

These goals were embodied in the portraits (see Fig. 4). The women often posed with a book or a newspaper while sitting on a chair wearing their çarşafs. The çarşaf was the most common form of outdoor clothing for Muslim women in early 20th-century Istanbul, varying in styles and colors. To facilitate Muslim women’s participation in professional life, members of the Association sought to standardize the çarşaf into a more practical and functional design that adhered to Islamic dress codes. By carrying intellectual objects like books or newspapers, donning a standardized çarşaf, and circulating their images through publication, the authors visually expressed their commitment to education, professional engagement, and reformed attire.

Through Kadınlar Dünyası, Muslim women not only asserted their presence in public discourse but also redefined how they were seen and understood. These portraits were more than individual representations – they were collective statements about modernity, agency, and the evolving role of Muslim women in Ottoman society.

Where have all the Ottoman Muslim Women Photographers gone?

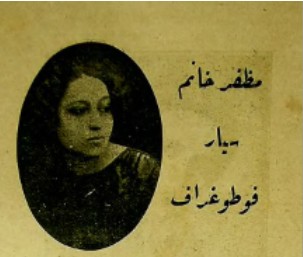

Women’s magazines are a unique source of information where the names and information about two Ottoman Muslim women photographers were mentioned: Naciye Hanım (Suman) (1881–1978) (see Fig. 3) and Muzaffer Hanım (?) (see Fig. 2). The advertisement of Naciye Hanım’s studio was published in Kadınlar Dünyası (1921).[6]

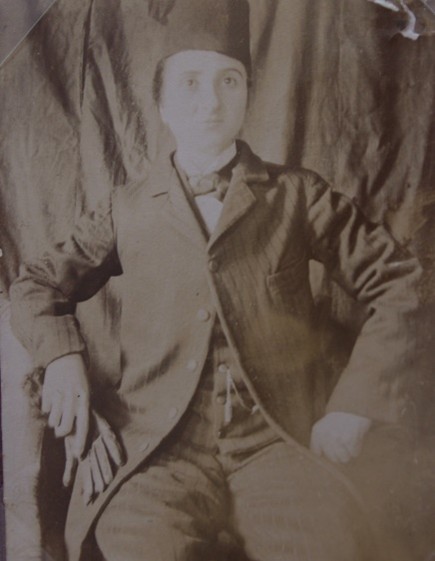

Two years later, the ads of the itinerant photographer Muzaffer Hanım were published in Süs magazine.[7] Lastly, another Ottoman amateur woman photographer: Hatice Şahiye Barlas (app.1873–1958) came to light thanks to a family biography written by her granddaughter.[8]

Interviews with descendants of Naciye Hanım and Hatice Şahiye Barlas (see Fig. 5) reveal that their photography was often seen as a means of survival or a personal hobby, rather than a professional pursuit. Consequently, their archives were rarely preserved. Naciye Hanım’s granddaughter noted that her career as a photographer was never discussed within the family, and no archives were saved. Luckily, Hatice Şahiye Barlas’s family preserved a small collection of her photographs, providing a rare glimpse into her photographic practices. Unfortunately, there is no further information on Muzaffer Hanım beyond the articles published in Süs magazine.

Final Thoughts

The invisibility of Ottoman Muslim women photographers is rooted in patriarchal norms that devalued women’s labor and limited their visibility in public spaces. While this invisibility creates a gap in understanding how Muslim women viewed themselves behind the lens, photography still offered a powerful medium for women to assert agency, negotiate societal expectations, and craft their self-representation. The analysis of the portraits and writings of the New Ottoman Muslim Woman demonstrates that these women sought to be active agents of modernization in the Ottoman civil sphere by utilizing accessible tools such as photography and printing.

Abbildungsverzeichnis

Fig. 1: The First Step to Progress by Ottoman Women (Osmanlı Kadınlığında Ilk Hutve-ı Terakki), Kadınlar Dünyası 117 (22 November 1913): Cover.

Fig. 2: Muzaffer Hanım Itinerant Photography (Muzaffer Hanım Seyyar Fotoğraf), Süs 2 (23 June 1923 [1339]): 15.

Fig. 3: Naciye Hanım, circa 1919. Courtesy: Gülderen Bölük Private Collection.

Fig. 4: The Greatest Poet Lady Yaşar Nezihe, Kadınlar Dünyası 124 (10 January 1914): Cover.

Fig. 5: Hatice Şahiye Hanım (app. 1900–1910). Courtesy: Mualla Mezhepoğlu Family Archive, 2019.

Anmerkungen

[1] Elizabeth Otto and Vanessa Rocco The New Woman International: Representations in Photography and Film from the 1870s through the 1960s (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012); Mary Louise Roberts, Disruptive Acts: The New Woman in Fin-de-Siecle France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004); Alys Eve Weinbaum, Lynn M. Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta G. Poiger, Madeleine Yue Dong, and Tani E. Barlow, The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (Duke University Press, 2008).

[2] Emine Hoşoğlu Doğan’s Ph.D. thesis is one of the unique scholarly works that uses the New Ottoman Muslim Woman as an analytical concept. In her dissertation, Hoşoğlu analyzes the writings of Ottoman Muslim women of letters to unpack the women’s agency in the modernization period. Emine Hoşoğlu Doğan, “Late Ottoman Muslim Women of Letters Vis-a-Vis The Gendered Discourse of “The New Ottoman Muslim Woman,” (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Utah, 2016).

[3] The collection includes approximately 37.000 images from the Imperial land and globe. It is accessible online through the library of Istanbul University. See here.

[4] “The First Step to Progress by Ottoman Women (Osmanlı Kadınlığında Ilk Hutve-ı Terakki),“ Kadınlar Dünyası 117 (22 November 1913): Cover.

[5] „Osmanlı Müdafaa-i Hukuk-ı Nisvan Cemiyeti Programı (The Program of the Association of Defending Ottoman Women’s Rights),“ Kadınlar Dünyası 55 (10 June 1913).

[6] „Naciye Hanım in Havadis-i Dünya,“ Kadınlar Dünyası 192 no.2 (8 Kânun-i Sani [January, 1921]): 11.

[7] „Mobile Photograph Lady Muzaffer (Seyyar Fotoğraf Muzaffer Hanım),“ Süs 8 (8 August 1339 [1923]): 15.

[8] Mualla Mezhepoğlu, Dün Takvimde Biter (Yesterday [only] Ends in the Calender), (Istanbul: İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2015).

Leave A Comment