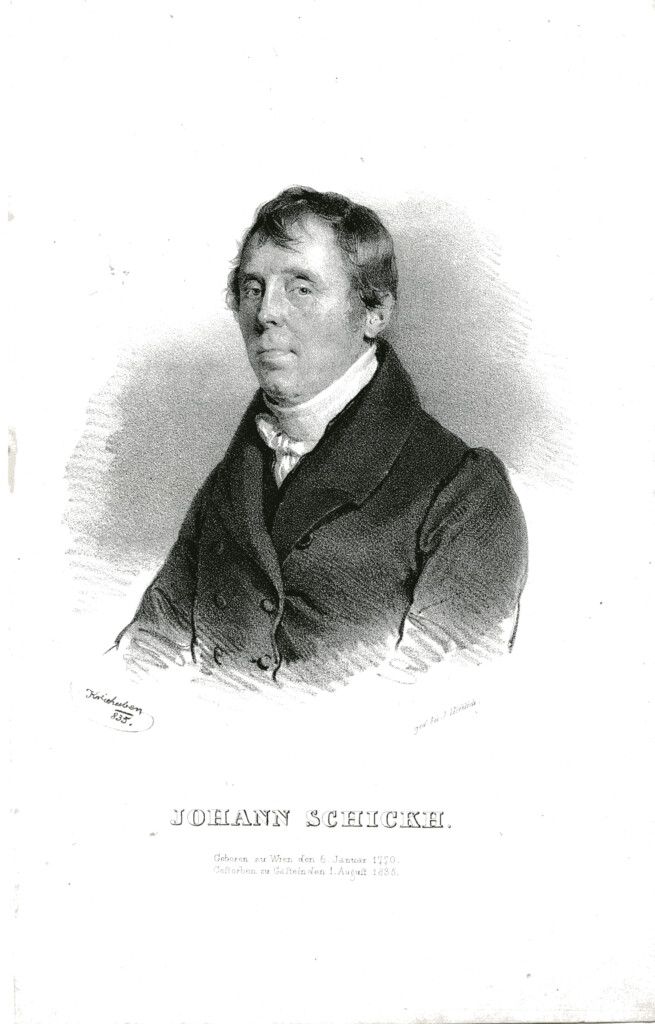

What women should wear was intensely debated in early 19th century Vienna. The city’s dressmakers strove to advertise their products and establish a consumer base for them. Thus, in 1816 Johann Schickh founded the first Viennese fashion magazine to promote a ‘Viennese fashion’, women should follow.

The ‘Wiener Moden-Zeitung’ was the first Viennese fashion magazine. It was founded in 1816 as a weekly publication by Johann Schickh, a tailor and man of letters. After a few months, the magazine was published twice a week, then gradually up to five times a week until its end in 1849.[1] The ‘Wiener Moden-Zeitung’ was evidently a successful undertaking on account of its longevity and increase in publication. The magazine addressed middle-class or bourgeois women, who could afford at least the quarter-year presubscription of fifteen Gulden W.W. It likewise circulated among the provincial bourgeoisie in the Austrian Empire, and did not give much space to male fashion.

Publications in the second half of the eighteenth century in Vienna, such as almanacks, pocket books or calendars, strove to demonstrate the latest fashions from abroad and addressed also producers of clothing, like seamstresses or milliners. The purpose of the Viennese fashion magazine according to its founder was to cultivate simpler, finer taste among its readers by presenting “the finest and most tasteful creations in female headdress, costume and furniture produced in Vienna”.[2] Thus, the readers should learn to appreciate domestic beauty, and to prefer these products to “tasteless and meritless foreign goods”.[3]

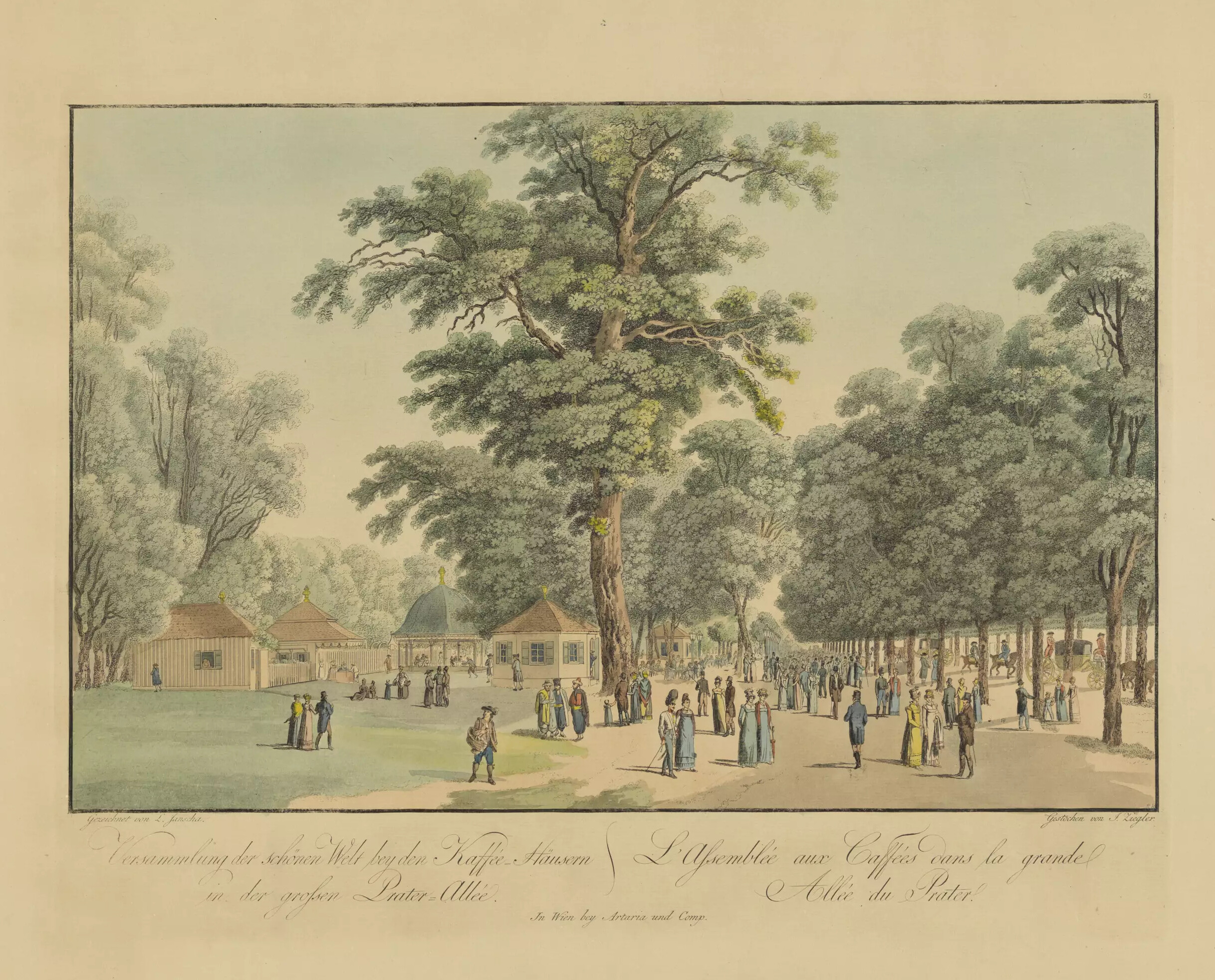

Changes in consumption in European societies and the discussions they instigated, particularly in the second half of the eighteenth century, constituted the social background in which the magazine was launched. According to historical research on consumption, female consumers, including working women with disposable income and the agency to make their own purchasing decisions, were important in explaining the increase in consumption in Europe in the eighteenth century. Fashion was key. Fashion in the eighteenth century was institutionalized into an industry, with its own spaces, calendar and media, and its dominant centers were Paris and London. Fashion constituted the principal criterion for consumption and dictated demand. Goods were ascribed fashionable qualities, and they were incorporated into lifestyles with broader associations.[4]

Fashion and Morals

Nevertheless, female consumption and particularly female appearance constituted an object of intense public debate. Since 1781 and the loosening of the censorship regulation by Josef II, brochures, essays and satirical works sparked a debate on the dress of the Viennese. It centered on economic and moral arguments. The critique of female consumers as morally loose prompted demands for restrictions, even the reenactment of long-obsolete sumptuary laws.[5]

This discussion, which continued in the following decades, should be viewed within the broader framework of the debates on luxury, which raged across Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In these debates, the merits and demerits of consumption were discussed on a moral, economic, political and social basis, and female consumption occupied a central position.

In the German territories, this discussion was often framed in moral terms according to which the simple, modest, agrarian Germans were corrupted by foreign influence, especially German women in big cities like Vienna.[6] Thus, in 1816 Vienna, the question of what women should wear and what an appropriate fashionable dress should look like was a heated topic. In his very first editorial, Johann Schickh set out to provide an answer to these issues.

A Story of Liberation

Inhis editorial in the first issue of the magazine, published 4 January 1816, and titled “A word on costume and fashion”,[7] Schickh propagated that the Viennese (women) abandon French dress and fashion, and associated this with the liberation from foreign rule during the recent wars against Napoleon. He scorned German men and women for spending their gold abroad for foreign clothes and frivolities, which he described as an afront to free Germans. Schickh argued that, in contrast to two centuries ago, when Germans adopted French fashions through a lustrous royal court, it was time they found their own voice and spirit in matters of dress, as they did in other sectors of social life.

Of a ‘German’ Taste

Schickh viewed fashion and its inherent change as an unavoidable part of human nature, which strove for the ideal of beauty. The principles of contemporary standards of beauty, which he similarly put forward, were harmony and symmetry. Already before the turn of the century, fashion moved away from aristocratic models of stilted dress, towards bourgeois ideals of simplicity and harmony between dress and body epitomized in a flowing dress cut with high waistline called ‘à la Grècque’.

A popular type of female dress across Europe was the ‘Chemise’, a dress with high waist, which was worn without a hooped skirt or a tight corset and formed a natural silhouette.[8] This was also the most popular type of dress in Vienna in the first decades of the nineteenth century. Schickh referenced the ancient Greek deities of beauty, the three Charites, to validate his view on fashion.

Schickh also argued that fashion should be compatible with the qualities, peculiarities and intellectual character of a nation. However, he did not perceive this as a national costume for all German people. This suggestion had been debated in the German-speaking world in the last decades of the eighteenth century and resurfaced in the 1810s in Viennese bourgeois salons brimming with anti-French sentiment.[9]

Schickh did not support a return to older, stale forms of dress. Rather, he postulated that a worthy goal should be the development of taste among the Germans which would consequently result in an end to following foreign trends, and to fostering forms more appropriate to this construed German character. The word ‘taste’ permeated the editorial. Schickh understood that taste was more important for designating what was fashionable and desirable than the quality of material or craftsmanship, commonly associated with luxury and social position.

He was not alone. Fashion magazines across Europe emphasized taste and employed similar arguments. In the eighteenth century, through commercialization, accessibility, the public sphere, the transmission of knowledge and, crucially, marketing to women taste in fashion became property of broader urban middle-class strata.[10] Schickh used not the quality of the advertised clothes and accessories as a sales-strategy, as the Viennese producers could not compete with their French counterparts, but national identity. He linked taste to a concept with collective appeal and could at the same time broaden his audience.

An Ingenious Viennese Milliner

As he elaborated further on the issue of German taste, Schickh followed a common line of argumentation in the debate on dress in the German territories. He described a grim reality, in which the honest and thoughtful German people, who placed emphasis on spirit rather than appearance, were forced to adopt fashions unsuitable to them, by the superficial and frivolous French.

To underline his tale of liberation from French creations, he told the success story of how a Viennese fashion item conquered Paris. He described French tall headdresses that came in fashion in 1811 as a distortion of noble forms and a relic of the aristocratic dress of the past. However, in 1814, at the height of this fashion trend in Paris and Vienna, the ingenious Viennese milliner Mr. Langer, probably not by accident a sponsor of the magazine, replaced the tall headdress with a shorter, and thus much more charming, headdress. Gradually, and after he sent illustrations of his work to Paris, the French adopted the short headdress as well. An outstanding accomplishment, as – according to Schickh – this was the first time in history, that the French followed the German example in matters of fashion.

“The Pride of the German Fatherland”

At the end of his editorial, Schickh brought his argument full circle and reiterated an image of war. Despite the efforts of the creative Viennese milliner, French assault on beauty would not cease. Thus, it was paramount that German women protected themselves from such danger and followed the parameters of harmony and symmetry. Once they had learned to appreciate domestic products in dress, they would no longer need foreign adornments and become “the pride of the German fatherland”.[11]

Female dress was a contested terrain. Schickh’s answer was not to advocate for restrictions in dress or for a national costume, but to steer women to a specific direction. Female dress became in his argument a matter of national honor and pride. For Schickh fashion was a battlefield, in which Germans must prevail.

Buy Local!

In his editorial, Schickh stepped up with the glorious purpose of liberating German (middle-class) women from French (aristocratic) yoke in dress and fashion. Nevertheless, the critical eye of the historian finds alternative motives. In the fashion industry, characterized by periodicity, producers’ and consumers’ access to information played a crucial role in product distribution and gaining market share. For tailors and manufacturers, the identification of a target audience, the creation of a consumer base, the timing of production, and marketing strategy were critical.[12] The Viennese fashion industry was at the time in its infancy and could not compete with London and Paris. It had to create its own consumer base. The Viennese middle class, in contrast to the nobles who could buy directly from abroad, was a suitable target audience.

The date of the first issue of the ‘Wiener Moden-Zeitung’ is another clue. After the Congress of Vienna (1814–15), due to the great influx of European nobles and their entourage, the number of Viennese producers increased significantly. In addition, they had been exposed to a variety of influences, gained expertise and honed their skills. Now, they needed to establish a consumer base for their products and an instrument for advertising.[13] Johann Schickh was, above all, an astute businessman, who understood the need for such an instrument at this crucial time, as well as the way this trade functioned. He delivered elaborately and presumably effectively a simple and timeless message: buy local!

Anmerkungen

[1] Hubert Kaut, Modeblätter aus Wien: Mode und Tracht von 1770 bis 1914 (Wien-München: Jugend und Volk, 1970), 48–50.

[2] “[D]er schönsten und geschmackvollsten Erzeugnisse der Kaiserstadt an Frauen-Kopfputz, Kleidertracht und Hausgerät (Möbeln)”. Wiener Moden-Zeitung, 4.1.1816. Kaut, 35–42; Gerda Buxbaum, Mode aus Wien, 1815-1938 (Salzburg und Wien: Residenz Verlag, 1986), 43–44.

[3] “[G]eschmack- und werthlosen Fremden”. Wiener Moden-Zeitung, 4.1.1816.

[4] Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb, The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England (London: Europa Publications Limited, 1982), 9–33; Jan De Vries, The Industrious Revolution: Consumer Behavior and the Household Economy, 1650 to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 122–85; Frank Trentmann, Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers from the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First (UK: Allen Lane, 2016), 53–77; Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 247–57.

[5] Kai Kauffmann, „Es ist nur ein Wien!“ Stadtbeschreibungen von Wien 1700 bis 1873: Geschichte eines literarischen Genres der Wiener Publizistik, Literatur in der Geschichte, Geschichte in der Literatur 29 (Wien-Köln-Weimar: Böhlau, 1994), 165–68, 178–82, 276–77; Leopoldine Springschitz, Wiener Mode im Wandel der Zeit: Ein Beitrag zur Kulturgeschichte Alt-Wiens (Vienna: Wiener Verlag, 1949), 25–31.

[6] Maxine Berg and Elisabeth Eger, “The Rise and Fall of the Luxury Debates,” in Luxury in the Eighteenth-Century: Debates, Desires and Delectable Goods, ed. Maxine Berg and Elisabeth Eger (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 18–19; Rainer Wirtz, “Kontroversen über den Luxus im ausgehenden 18. Jahrhundert,” Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte / Economic History Yearbook 37, no. 1 (1996): 165–75.

[7] “Ein Wort über Kleidertracht und Mode”. Wiener Moden-Zeitung, 4.1.1816.

[8] Aileen Ribeiro, Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe 1715-1789 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002), 226–28; Jutta Zander-Seidel, Kleiderwechsel: Frauen-, Männer- und Kinderkleidung des 18. Bis 20. Jahrhunderts (Nürnberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2002), 59–64.

[9] Michael North, “Kultur und Konsum – Luxus und Geschmack um 1800,” in Geschichte des Konsums: Erträge der 20. Arbeitstagung der Gesellschaft für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 23.-26. April 2003 in Greifswald, ed. Rolf Walter (Germany: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004), 30–32; Springschitz, Wiener Mode im Wandel der Zeit: Ein Beitrag zur Kulturgeschichte Alt-Wiens, 65–72.

[10] Jennifer M. Jones, “Repackaging Rousseau: Femininity and Fashion in Old Regime France,” French Historical Studies 18, no. 4 (1994): 947–63; North, “Kultur und Konsum – Luxus und Geschmack um 1800,” 27–32; Daniel Purdy, “Modejournale und die Entstehung des bürgerlichen Konsums im 18. Jahrhundert,” in Der lange Weg in den Überfluss: Anfänge und Entwicklung der Konsumgesellschaft seit der Vormoderne, ed. Michael Prinz (Paderborn-Wien: Schöningh, 2003), 219–30; Evelyn Welch, “Introduction,” in Fashioning the Early Modern: Dress, Textiles, and Innovation in Europe, 1500-1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 14–26.

[11] “[D]er Stolz des deutschen Vaterlands”. Wiener Moden-Zeitung, 4.1.1816.

[12] John Styles, “Fashion and Innovation in Early Modern Europe,” in Fashioning the Early Modern: Dress, Textiles, and Innovation in Europe, 1500-1800, ed. Evelyn Welch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 33–55.

[13] Springschitz, Wiener Mode im Wandel der Zeit: Ein Beitrag zur Kulturgeschichte Alt-Wiens, 57–61; Roman Sandgruber, Die Anfänge der Konsumgesellschaft: Konsumverbrauch, Lebensstandard und Alltagskultur in Österreich im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert (Vienna: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, 1982), 301–2.

Kommentar schreiben